The story of organization begins not with computers or cloud storage, but with ingenious paper-based systems that revolutionized how humanity managed information and knowledge.

📂 The Dawn of Organized Information Management

Before the digital revolution transformed our world, businesses, governments, and institutions faced a monumental challenge: how to store, retrieve, and manage ever-increasing volumes of paper documents. The evolution of filing systems represents one of humanity’s most practical innovations, bridging the gap between chaos and order in information management.

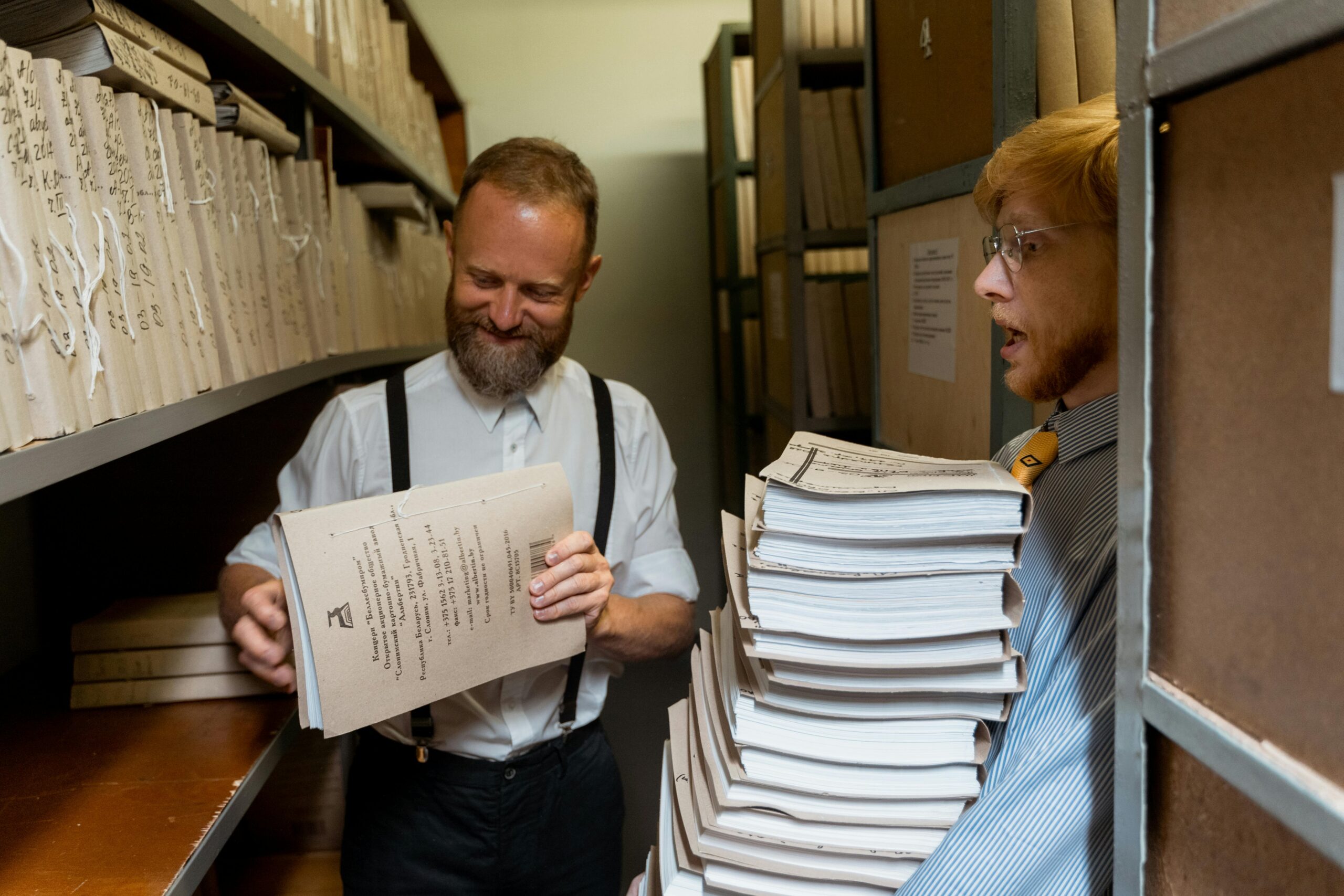

In the mid-19th century, offices were drowning in paperwork. Documents were stacked in piles, stuffed into boxes, or impaled on spikes—crude methods that made retrieval time-consuming and often impossible. The industrial revolution’s expansion created an urgent need for better organization, spurring inventors and office managers to develop systematic approaches to document management.

The Alphabetical Revolution That Changed Everything

The alphabetical filing system emerged as the cornerstone of modern organization. While alphabetizing seems intuitive today, its widespread adoption as a filing methodology represented a significant intellectual leap. This system allowed clerks to locate documents in seconds rather than hours, dramatically improving office efficiency.

Edwin G. Seibels, a South Carolina insurance agent, is credited with pioneering the vertical filing system in the 1890s. His innovation involved storing documents upright in drawers with labeled tabs, replacing the horizontal stacking method that had dominated for centuries. This simple change revolutionized accessibility and space efficiency.

The vertical filing cabinet became an icon of office culture, its design refined by companies like Shaw-Walker and Library Bureau. These cabinets featured sliding drawers, suspension folders, and guide cards—innovations that seem mundane today but were groundbreaking at the time.

🗄️ The Ingenious Dewey Decimal Classification

Melvil Dewey’s classification system, introduced in 1876, demonstrated how numerical organization could complement alphabetical methods. Originally designed for libraries, the Dewey Decimal System organized knowledge into ten main classes, with infinite subdivisions possible through decimal notation.

This hierarchical approach influenced filing systems beyond libraries. Businesses adapted the concept, creating numbered filing systems that allowed for expansion and reorganization without disrupting the entire structure. The principle of hierarchical classification remains fundamental to modern database design and digital folder structures.

Key Features of the Dewey System’s Influence

- Hierarchical organization allowing infinite subdivision and expansion

- Numerical notation that transcended language barriers

- Relative indexing that placed related subjects near each other

- Flexibility to accommodate new categories without restructuring

- Standardization that enabled universal understanding across institutions

The Color-Coding Innovation in File Management

As filing systems matured, practitioners discovered that human visual processing could be leveraged for faster retrieval. Color-coded filing systems emerged in the early 20th century, adding another dimension to organizational strategies.

Medical offices pioneered color-coding to distinguish patient files by year, status, or department. Law firms adopted similar systems to categorize cases by type or urgency. The psychological impact of color made misfiled documents immediately apparent—a red folder among blue ones stood out instantly, reducing errors.

This innovation acknowledged an important truth: effective organization must align with human cognitive strengths. Color-coding reduced mental load and accelerated decision-making, principles that UX designers still apply in digital interfaces today.

⏰ The Chronological Filing Method and Time-Based Organization

Not all information is best organized alphabetically or by subject. The chronological filing system arranged documents by date, proving essential for industries where temporal sequence mattered—accounting, legal proceedings, medical records, and project management.

The tickler file system, a chronological variant, revolutionized task management in the pre-digital era. Consisting of 43 folders (31 for days, 12 for months), this system provided a physical reminder system for follow-ups, deadlines, and recurring tasks. Professionals would “tickle” future dates by filing reminders in appropriate date folders.

This concept directly influenced modern digital reminder systems and calendar applications. The principle remains unchanged: organize information by when action is needed, not just by what the information contains.

The Geographical Filing System for Expanding Enterprises

As businesses expanded geographically, organizing information by location became crucial. The geographical filing system arranged documents by country, region, state, city, or even neighborhood—whatever geographical hierarchy made operational sense.

Sales organizations found this particularly valuable, organizing customer files by territory to support regional sales representatives. Shipping companies organized manifests by destination. Government agencies structured records by jurisdiction. The geographical approach recognized that physical location often determined relevance and responsibility.

Combining Multiple Filing Principles

Sophisticated organizations rarely relied on a single filing method. Instead, they developed hybrid systems combining multiple principles. A law firm might organize files first by practice area (subject), then by client name (alphabetical), then by case date (chronological).

| Filing Method | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage | Modern Digital Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alphabetical | Name-based retrieval | Intuitive and universal | Sorted lists and directories |

| Numerical | Large-volume systems | Infinite expansion capacity | Database primary keys |

| Subject/Categorical | Topic-based research | Groups related information | Folder hierarchies and tags |

| Chronological | Time-sensitive documents | Reflects sequence of events | Timeline views and date filters |

| Geographical | Location-based operations | Aligns with territorial structure | Location-based filters and maps |

📋 The Index Card Revolution and Information Atomization

Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist, pioneered the use of index cards in the 18th century to organize botanical specimens. This seemingly simple innovation—recording one piece of information per card—revolutionized knowledge management by making information modular and reorganizable.

The index card system allowed scholars and professionals to sort and resort information without rewriting entire ledgers. Ideas could be physically shuffled, grouped, and regrouped—an analog version of what we now do digitally with databases and digital notes.

Libraries adopted card catalogs as their primary access system, with millions of cards meticulously typed and filed. The standardized 3×5 inch card became ubiquitous in offices, schools, and research institutions worldwide. Writers used index cards to outline novels. Detectives used them to organize case clues. Scientists used them to record experimental observations.

The Standardization Movement and Universal Principles

As filing systems proliferated, the need for standardization became apparent. Organizations developed filing manuals, and professional associations established best practices. The National Association of Office Managers (later part of ARMA International) promoted standardized filing rules.

Standardization addressed practical challenges: How should names beginning with “Mc” be filed? Where do acronyms belong? Should “The” count in alphabetization? These seemingly minor decisions had major implications for system-wide consistency and retrieval efficiency.

This standardization drive parallels modern efforts to establish data standards, metadata schemas, and information architecture principles. The underlying goal remains identical: enable consistent organization that multiple people can understand and maintain.

🔐 Security and Access Control in Physical Filing Systems

As filing systems became sophisticated, so did concerns about security and confidentiality. Organizations developed ingenious methods to protect sensitive information while maintaining accessibility for authorized personnel.

Locked filing cabinets with distributed keys represented the most basic security measure. More sophisticated systems used color-coding to indicate sensitivity levels—red labels for confidential, yellow for restricted, green for public. Some organizations implemented check-out systems, requiring users to sign for files and documenting who had accessed what information.

These physical access control mechanisms prefigured modern digital permissions systems. The concepts of authentication (proving who you are), authorization (determining what you can access), and audit trails (recording who accessed what) all originated in physical filing system management.

The Microfilm Revolution and Space Efficiency

By the mid-20th century, successful organizations faced a new problem: their excellent filing systems created so much accessible information that physical storage space became prohibitively expensive. Microfilm and microfiche emerged as solutions, shrinking documents to tiny images on film.

A single microfilm reel could store thousands of document pages, reducing storage space by 95% or more. Specialized readers magnified the images for viewing. While requiring equipment for access, microfilm systems maintained the organizational principles of the paper systems they replaced—documents were still indexed alphabetically, numerically, or chronologically.

Microfilm represented an intermediate step between paper and digital storage, demonstrating that information organization principles remain valid across technological transformations. The metadata, indexing, and classification schemes translated from paper to film, and later from film to digital formats.

💡 Lessons from Physical Filing Systems for Digital Organization

The transition from physical to digital storage hasn’t eliminated organizational challenges—it has simply transformed them. Many problems modern knowledge workers face with digital information management were solved decades ago in physical filing systems.

Digital file systems often fail because users ignore fundamental organizational principles that filing clerks considered essential. A computer folder structure labeled “Miscellaneous,” “Old Stuff,” and “Important” reflects the same chaos that paralyzed 19th-century offices before systematic filing emerged.

Timeless Principles from Early Filing Systems

- Consistency matters more than perfection—a consistently applied imperfect system outperforms an inconsistently applied perfect one

- Classification schemes must reflect how information will be retrieved, not just how it was created

- Systems must accommodate growth without requiring complete reorganization

- Visual cues accelerate navigation and reduce cognitive load

- Metadata and indexing are as important as the documents themselves

- Access control must balance security with usability

- Regular maintenance prevents system degradation over time

The Human Element in Organizational Systems

Early filing systems succeeded or failed based on human factors: training, discipline, and cultural adoption. The most elegant filing system was worthless if employees didn’t understand it, didn’t follow it consistently, or actively resisted it.

Progressive organizations invested in training programs for filing clerks, recognizing that these employees were information gatekeepers whose expertise determined organizational efficiency. Professional file clerks developed remarkable skill in quickly locating documents, understanding cross-references, and maintaining system integrity.

This human dimension remains critical in digital environments. Technology can facilitate organization, but humans must still decide how to classify information, maintain consistency, and ensure the system serves its users rather than becoming a bureaucratic burden.

🌉 Bridging Past and Present: Physical Principles in Digital Tools

Modern productivity applications embody principles invented for paper filing systems. Tags function like cross-reference cards. Search features simulate the index card catalog. Hierarchical folder structures mirror the classified filing systems of the early 20th century.

Note-taking applications have rediscovered the power of atomic information units—the index card principle. Digital zettelkasten methods, networked note-taking, and personal knowledge management systems all build on organizational concepts developed long before computers existed.

Calendar applications are essentially digital tickler files. Project management tools combine chronological, categorical, and geographical organization. Customer relationship management systems often default to alphabetical organization by company name, just as Rolodexes did.

The Enduring Legacy of Filing System Innovation

The ingenuity of early filing system pioneers laid foundations that extend far beyond dusty file cabinets. Their innovations addressed fundamental human needs: to preserve knowledge, locate information efficiently, and build on past work rather than constantly starting from scratch.

Every database query, every search algorithm, every information architecture ultimately traces back to principles established by individuals trying to organize paper documents more effectively. The shift from physical to digital hasn’t replaced these principles—it has amplified their importance while making violations of good organizational practice easier and more consequential.

Understanding the evolution of filing systems provides perspective on modern information management challenges. The problems aren’t new; the storage medium has changed, but human cognitive limitations, organizational challenges, and the fundamental need for retrievable information remain constant.

📚 From Filing Cabinets to Cloud Storage: The Continuous Thread

Today’s cloud storage systems, with their folders, tags, and search functions, represent the latest chapter in a story that began with vertical file cabinets and index cards. The vocabulary has evolved—we speak of directories rather than drawers, metadata rather than guide cards—but the conceptual framework remains recognizable.

The most successful modern organizations combine digital tools with organizational discipline derived from pre-digital era practices. They establish naming conventions, classification schemes, retention policies, and access controls—all concepts refined through decades of physical filing system management.

Looking forward, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning promise to automate aspects of information organization. However, these systems still require underlying structures based on principles developed when filing meant physically placing paper in drawers. The past isn’t merely prologue—it’s foundation.

The evolution of filing systems demonstrates that innovation often comes from solving practical problems with available tools. The individuals who developed alphabetical filing, vertical storage, color-coding, and chronological organization weren’t technology visionaries—they were practical problem-solvers addressing immediate needs. Yet their solutions shaped how billions of people organize information today, proving that the most enduring innovations often come from addressing fundamental human needs with clarity, consistency, and ingenuity. Their legacy lives in every organized digital folder, every searchable database, and every efficiently managed information system in the modern world.

Toni Santos is a legal systems researcher and documentation historian specializing in the study of early contract frameworks, pre-digital legal workflows, and the structural safeguards embedded in historical transaction systems. Through an interdisciplinary and process-focused lens, Toni investigates how societies encoded authority, accountability, and risk mitigation into documentary practice — across eras, institutions, and formalized agreements. His work is grounded in a fascination with documents not only as records, but as carriers of procedural wisdom. From early standardization methods to workflow evolution and risk reduction protocols, Toni uncovers the structural and operational tools through which organizations preserved their relationship with legal certainty and transactional trust. With a background in legal semiotics and documentary history, Toni blends structural analysis with archival research to reveal how contracts were used to shape authority, transmit obligations, and encode compliance knowledge. As the creative mind behind Lexironas, Toni curates illustrated frameworks, analytical case studies, and procedural interpretations that revive the deep institutional ties between documentation, workflow integrity, and formalized risk management. His work is a tribute to: The foundational rigor of Early Document Standardization Systems The procedural maturity of Legal Workflow Evolution and Optimization The historical structure of Pre-Digital Contract Systems The safeguarding principles of Risk Reduction Methodologies and Controls Whether you're a legal historian, compliance researcher, or curious explorer of formalized transactional wisdom, Toni invites you to explore the foundational structures of contract knowledge — one clause, one workflow, one safeguard at a time.